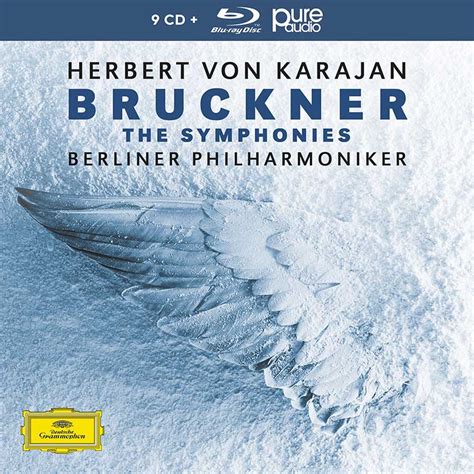

The Anton Bruckner symphony cycle recorded by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan (the Wing Cycle to some collectors) has long been known to me and cherished. Based on Amazon reviews noting remastered and improved sound over previous releases of the same recorded performances, I decided the relatively low cost was worth trying out Blu-ray Audio, my first such disc. Although the entire cycle fits on a single Blu-ray Audio disc, nine CDs are included in the box. Duplication seems unnecessary, but the inclusion of both may be desirable for some listeners. Pleasingly, original cover art (the aforementioned wing) from the LPs appears on the 2020 rerelease. Shamefully, like another recent set of Bruckner symphonies, DG put the conductor’s name above the composer’s. This practice ought to stop. This review is about comparing versions/media in addition to reviewing the performances. Caveat: a superior stereo system is a prerequisite. If listening on some device not intended for high fidelity (phone, computer, etc.), save your dollars and find the recordings on a streaming service. Both CD and Blu-ray players in my system are connected to the preamp via digital cables to use the better DAC in the preamp rather than those in the players.

The Anton Bruckner symphony cycle recorded by the Berlin Philharmonic under Herbert von Karajan (the Wing Cycle to some collectors) has long been known to me and cherished. Based on Amazon reviews noting remastered and improved sound over previous releases of the same recorded performances, I decided the relatively low cost was worth trying out Blu-ray Audio, my first such disc. Although the entire cycle fits on a single Blu-ray Audio disc, nine CDs are included in the box. Duplication seems unnecessary, but the inclusion of both may be desirable for some listeners. Pleasingly, original cover art (the aforementioned wing) from the LPs appears on the 2020 rerelease. Shamefully, like another recent set of Bruckner symphonies, DG put the conductor’s name above the composer’s. This practice ought to stop. This review is about comparing versions/media in addition to reviewing the performances. Caveat: a superior stereo system is a prerequisite. If listening on some device not intended for high fidelity (phone, computer, etc.), save your dollars and find the recordings on a streaming service. Both CD and Blu-ray players in my system are connected to the preamp via digital cables to use the better DAC in the preamp rather than those in the players.

My comparison involves four releases of the cycle: (1) original LPs from the 1970s and 80s, (2) 1990 CDs, (3) 2020 CDs, and (4) the sole 2020 Blu-ray Audio disc. All are the same works and same performances. Direct A/B/C/D comparisons are difficult, and I didn’t listen to every version of each, which would have required far too many hours. Rather, I focused on two representative movements well established in my ear: the 2nd movt. (Adagio) of the 5th and the 4th movt. (Finale) of the 8th. Because every recording has its own unique characteristics borne out of the era (typically divided by decade), the engineering team, and the producer, it’s normal for me to attempt to “hear through” all the particulars of a recording to the actual performance. For a recording to be badly flawed or unlistenable is fairly exceptional, and I still tend to make mental adjustments to accommodate what I’m hearing. Similar perceptual adjustments in the visual spectrum known as “white balance” reflect how outdoor lighting and color shift as the sun transits across the sky. Accordingly, there is probably no such thing as authentic or natural sound as one’s perceptual apparatus adjusts automatically, accommodating itself to what is heard to fit circumstance. That said, it’s obvious that some recorded media and listening environments are superior to others.

Easy part first: comparison of (2), (3), and (4) revealed only minor differences at best. A tendency toward bright, treble-heavy equalization was not ameliorated with (3) or (4) as other reviewers suggested remastering had accomplished. With the 4th and 9th symphonies especially, sustained timpani rolls often mask the orchestra and were not appreciably rebalanced or improved. For ease or due to laziness, I tend to cue CDs before any other media. The Blu-ray disc offers substantially the same sound but lumps all the tracks together in one extended, numbered sequence (no track titles). Selecting a particular track is a minor inconvenience and requires the TV screen be on, at least initially. Given that, CDs will likely continue to be the first medium I reach for. Perceptual accommodation may also account for my inability to detect much difference among any of the CDs and/or Blu-ray Audio. However, no surprise to audiophiles and despite their drawbacks, LPs proved to be the warmest, most pleasing sound. A huge amount of gain (volume) was needed to bring the LPs up to the sound level of other media, which overcame surface noise handily. Of course, LPs wear and become distorted over time, and quality of the playback equipment matters quite a lot. But for focused listening sessions, LPs win the media challenge handily.

Hard part second: these performances are remarkable for two principal reasons, namely, consistently excellent (even definitive, some say) interpretations and uniformly sumptuous orchestral sound. Karajan is renowned for his three Beethoven symphony cycles and how he grasps and communicates structure far better than most. The quality is subtle but unmistakable, and the same is true with Bruckner. Like Wagner, Bruckner performance style has developed into a cult of slow in two aspects: passages best realized at surprisingly slow tempos (difficult to maintain and control) and the stately pace at which symphonic form and discussion unfolds. Many individual movements top 20 min. in duration. The Berlin Philharmonic handles them exceptionally well, meaning without apparent impatience or hurry. The Adagio of the 5th is one such example, where the slow introduction exhibits breadth and beauty of tone and critical evenness of pulse (pizzicati in the low strings). Although quite slow, the intro holds one’s attention without flagging, meandering, or luring listeners away toward more obvious excitements. The string tutti that follows immediately is among several passages in Karajan’s recorded oeuvre that overcompensates (for what is unclear) in glorious fashion. My LP is decidedly worn from repeat playing of this movement. No other recording of the 5th (to my knowledge) dares to approach Berlin’s volume and intensity in these first few minutes. Similarly, the Finale of the 8th barrels in with a declamatory tutti that has never sounded better. Everything about this movement works to the credit of the Berlin Philharmonic, especially when the orchestra slots into an ideal combination of tempo and balance at 5:45. This particular passage rarely fails to inspire me, but no other recording captures quite the same authority. Similarly, the gorgeous Wagner tuba solo in the Adagio of the 8th and the rolling, swinging momentum of the Scherzo of the 8th, through many iterations of the same basic motif, are achievements unmatched by other recordings. Further observations could be made throughout the cycle, specifying moments that remain unparalleled.

Overall, none of the symphonies in the Wing Cycle is weak. Each possesses Karajan’s characteristic, dignified approach. Worth noting is that numerous flubs and misalignments are left in, which some critics assess as sloppiness — a quintessential characteristic often mentioned regarding Karajan recordings. To note counters, these represent unforgivable errors to be covered by retakes and/or editing. However, this human quality, audibly distinct from the overproduced and heartlessly punctilious perfection of many modern recordings (especially multitrack, quantized recordings found in pop and rock music), does not detract. Rather, a certain verisimilitude is presented, just like live performance. Truly being in the moment means accepting minor flaws to preserve the larger musical flow. Maybe this is how Karajan embodies a structural vision of the works, obliterated in other recorded performances by piecing together too many disparate parts. Hard to say.

Digressing somewhat, three orchestras dominate the field when it comes to recordings of Bruckner symphonies: the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (BPO), the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (VPO), and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The BPO and VPO are similar in approach and sound and are well represented in their respective discographies. (The VPO lacks a unified cycle under one conductor.) However, the CSO achieves its fairly unique results with this repertoire through an unusually high level of technical mastery — both individually and in aggregate — and through sheer, overwhelming, even outrageous volume and focus in the tuttis, led by the storied CSO brass section. Critics may complain of brass players swamping the orchestra and turning the whole endeavor into a wind symphony, such an overweening approach being better suited to overt hysterics of Russian symphonists such as Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich. That judgment is rather reductive, considering how Bruckner scored his orchestral works with ample time devoted to each section of the orchestra. As performer and brass player, the blazing thrills delivered by the CSO (in its heyday) have an extraordinary pull on my musical sensibilities.

The CSO’s two cycles under Barenboim and Solti are less consistently good than the Wing Cycle, but when individual entries are good, they’re very good indeed. For instance, the opening horn solo of the 4th (CSO under Barenboim) is perfection, as is the amazing modulating chorale undergirded by the tuba later in the movement. The main climax of the Adagio of the 4th (still CSO under Barenboim) is probably the most exuberant, shattering symphonic climax I’ve ever heard (Shosti 7 under Bernstein may exceed it but only by virtue of the double brass section). Solti’s highlights are the extended coda of the Finale of the 5th, the coda of the 1st movt. of the 9th, and nearly the whole of the 6th for its raw power and precision. Lots of other recordings I could mention, including Giulini’s two remarkable 9ths (frankly terrifying with the CSO but more cosmic with the VPO). The only orchestras that match the CSO for power and intensity are the BPO and VPO. However, European orchestras perform differently together and seldom display the same technical brilliance or volume of American orchestras. Instead, they sound more soulful. These characteristics are impossible to quantify, like the sound of LPs vs. CDs, but are readily apparent upon hearing. Further, both are valid approaches, able to satisfy musical tastes and objectives differently.

Von Karajan was a noted egomaniac, sometimes his picture – usually a close-up – adorning his album covers as well his name in bold font! In my view, as his career entered it’s later stages, the quality of his conducting eroded, as did the general recording quality. Berlin is sounding better without him. A notable exception would be his definitive rendering of ‘Das Lied von der Erde’ with Rollo and Ludwig vocals. I’m neither a musicologist nor a musician, but I know my Mahler!…Yes, I’m one of those.

Avoided the biographical angle on Karajan; someone inevitably brings up political connections leading to his appointment in Berlin. I also have his recording of Das Lied von der Erde but have never warmed to it or any other of his Mahler recordings (oddly incomplete symphony cycle). Whether for better or worse, the Berlin Phil has lost the distinctive qualities of the Karajan era. Can also be said of other orchestras with long tenures under music directors who defined their sounds.