While the larger focus of an article by Jennifer Palmer called “Zombie Apocalypse” is deconstructing our weird zombie fetish in entertainment, the best part is the discussion of a curious term: the uncanny valley. The term finds its origin in robotics (in 1970, according to the Wikipedia article). Although purely theoretical and lacking scientific support, even the soft science of psychology, it goes a long way toward explaining a wave of revulsion we typically feel as objects of our own creation approach realistic human likeness just before they become indistinguishable from real humans.

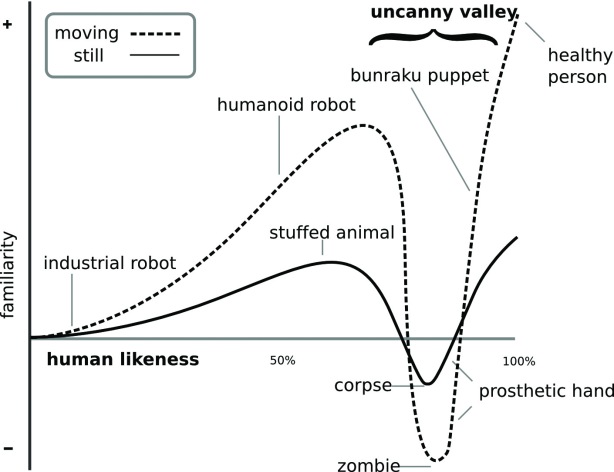

The theory states that as an object begins to acquire human characteristics, those characteristics stand out from its nonhumanness and we empathize with it. As it begins to look too human but is still recognizably nonhuman, the nonhuman characteristics stand out and we feel revulsion. Once we can no longer tell the robot or doll from a human, we again feel empathy. The valley between the tops of the two empathetic curves is uncanny precisely because humanness is too closely yet imperfectly imitated. The theory draws inspiration from an essay by Sigmund Freud called “The Uncanny.” This graph, unscientific as it is, plots the effect and several objects:

I draw attention to the lack of science to support the theory, but it nonetheless deals with some very real effects we experience and witness with dolls, animation, robots, corpses, and yes, even zombies. Artists who create life-like human forms that blend into crowds at art museums play on this effect. In animation, styled human movement (or animal movement, as is often the case) poses no trouble, but purely CGI characters (as in Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, I Robot, etc.) cause varying levels of discomfort. Those of us who contemplate a possible future with very life-like robots find the idea of it more than a little bit ooky. As for the rest of “Zombie Apocalypse,” I think the author is having a great deal of fun finding cultural touch points in mere popular entertainment, but like the theory of the uncanny valley, it lacks rigor. She still turns our heads by assigning familiar meanings to our fetish for zombies in entertainment:

… as a metaphor, a zombie apocalypse resonates strongly with many of our repressed fears and notions in the wake of September 11th. As an experience, acting out a zombie apocalypse is a way of participating in the kind of viral “outbreak” that mirrors the proliferation of the internets through which many of us live our lives …

Invoking 9/11? Really? It’s not as though our preoccupation with zombies (and vampires and superheroes) doesn’t long predate 9/11. Everything gets reinterpreted in the wake of 9/11, but this is too big a stretch.

The acting out she refers to are staged zombie walks/crawls with people dressed, made up, and acting like zombies on public streets — complete with fake blood and designated victims. As a stunt, it reminds me of the frozen people in Grand Central Station. Nonparticipants in the crowd for both stunts reacted with mild astonishment but otherwise went on about their business. (There may well be a real-life tragedy in the making with these stunts, based on public desensitization along the lines of The Boy Who Cried Wolf.)

Here is another of Jennifer Palmer’s assigned meanings:

The zombie trend is a celebration of fear — a way to paradoxically act out the suffocating effect that the blanket of information noise has in our Westernized, late capitalist existence.

And another:

Zombies represent the fear of being devoured by the Other — of being consumed or subsumed by an enemy who secretly lives among us and shares aspects of our appearance but is drastically and grotesquely inhuman in a way that curtails any possible communication.

And yet another:

The zombies also represent the fear of being turned into mindless slaves by our own technology à la The Matrix, as we move into an age of linked-together knowledge systems that makes us nodes on our own network.

None of these rings especially false, but neither do these pseudorevelations offer anything that couldn’t be better understood from any number of better informed perspectives. Rather, her analysis strikes me as the product of an idle, decadent class of pop-kitsch fanboys (and girls) who strain too hard to find significance in their entertainment obsessions. In a similar vein, Roger Ebert angered gamers by insisting that video games cannot be considered art. (Movies based on video games blur distinctions even further, but then, not all movies are legitimately cinema, either.) New Critics, where I sometimes comment, also offers an endless stream of breathless fan reports on the authors’ favorite shows, albums, celebrities, etc. It’s certainly a cut above most pop culture websites obsessed with clothing, he said/she said, and boobs, and New Critics authors aren’t exactly screaming 14-year-old girls insisting that “Britney rules” (despite a growing heap of evidence to the contrary), but there is still something unseemly about adults waxing rhapsodic over zombies, rockers, movie stars, TV shows, movies, etc. as cultural signifiers. Perhaps the war in Iraq, for which we’re indirectly responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths, might be a better source of revulsion to rivet our attention.

now, why are some folks fascinated with death, corpses? not necessarily because they are sick, as in psycho sick. some medical doctors deal with dead bodies. what do you call them? pathologists? why are dead human bodies so fascinating? because in looking at a dead human body, we are looking at what we might look like when we are dead? morbid thoughts.

okay, let’s start over. let’s say we have a little baby who is old enough to appreciate stuffed animals. she takes her little meow meow or wuff wuff or bear and snuggles it. what do those fuzzie wuzzies represent to her? love? comfort? are those human traits being transfered to inanimate animals? do these fuzzie wuzzies provide unconditional love, something maybe a bit too elusive as the child gets older? hmmm. sumpin to tink ’bout.

OCMR, I might like to respond to what you’re saying, but I can’t really figure out what you’re musing about. Your comment doesn’t really track to what I posted. It’s not word salad, exactly, and you do drop in a couple important keywords, but what is it that you’re saying?

stream of consciousness, brutus. that’s what i am all about. sorry if i am too deep for you.

On the contrary, your stream of consciousness is rather shallow and uninsightful. I’m all about critical thinking. The comments you have posted under a variety of names offer me nothing on which to comment. You can disagree with me, add something interesting, or develop an idea I present. That’s worthwhile. Rambling, mental wandering, and unfocused musing don’t really interest me much. YMMV, obviously, and I can only speak for myself.

i’ve got bigger fish to fry than give you any more time of my day. goodbye, brutus.

While this will add nothing to the discourse, or lack thereof, in this particular comments thread….

I doubt that “ocmr” has a bigger one than I do.

Yet, I seem to have plenty of time to fry it. All the while maintaining a fair, (albeit tenuous,) grasp of the concept of proper sentence structure.

Perhaps he/she has created a new paradigm in the realm of stream of consciousness writing and I am just not “hip” enough to be able to recognize it

To be fair to omcr, I am also apparently not hip enough to discontinue using capitals at the beginning of my sentences…

There should have been a photo of a big ole fish accompanying my post to add some bit of levity to it.

I am sorry if my post may seem overly condescending without it’s addition.